The Rev. Peter Jenks reflects on his long tenure in Thomaston

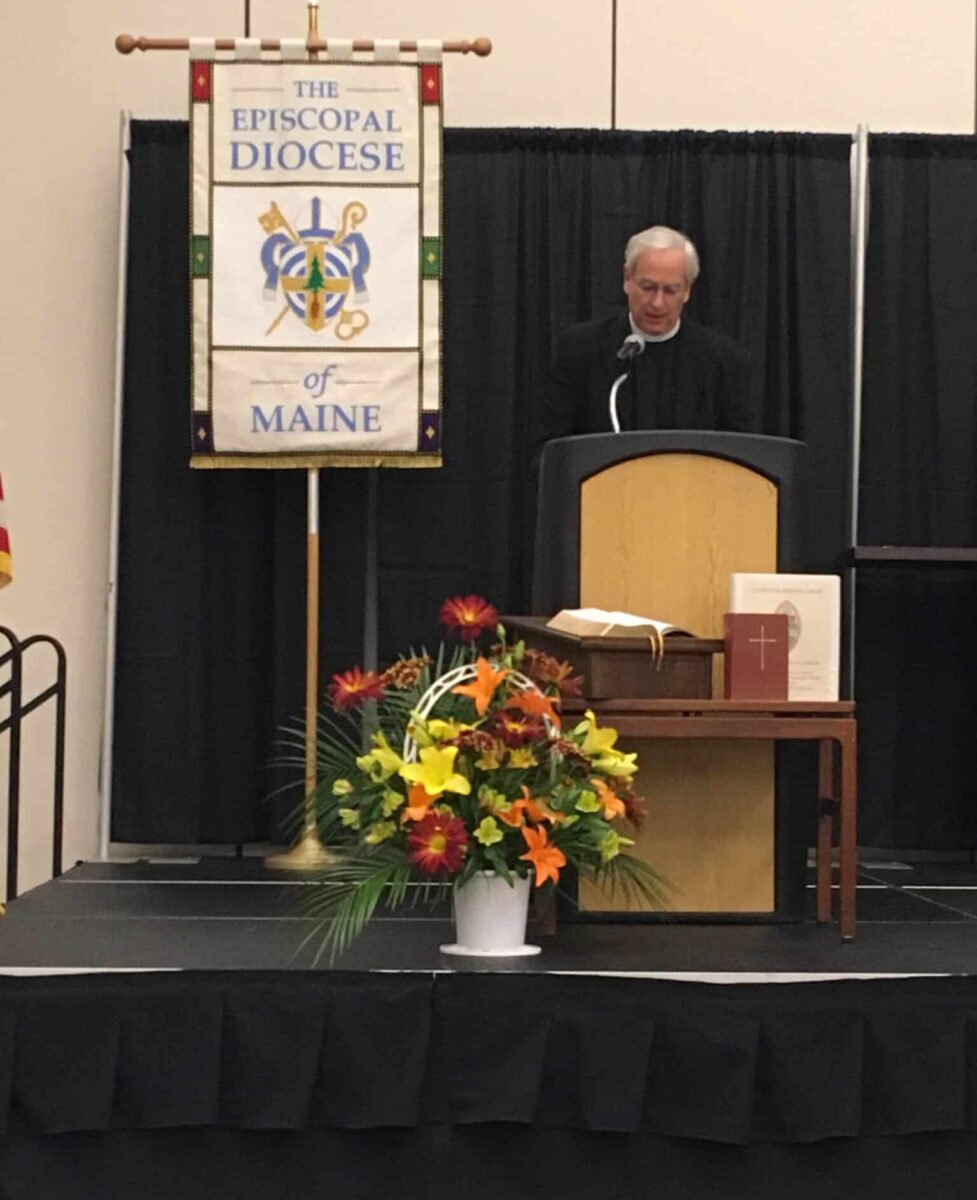

When he retires from the Episcopal Church of St. John Baptist in Thomaston on Sept. 29, Rev. Peter Jenks will leave a legacy that spans five bishops and more than three decades. He’s the longest-serving priest in the diocese but says that doesn’t give him seniority or any kind of special status. “It just means I’ve been in one place for a long time,” he says. “I talk about being a long-term pastor, much of that is that I’ve shown up.”

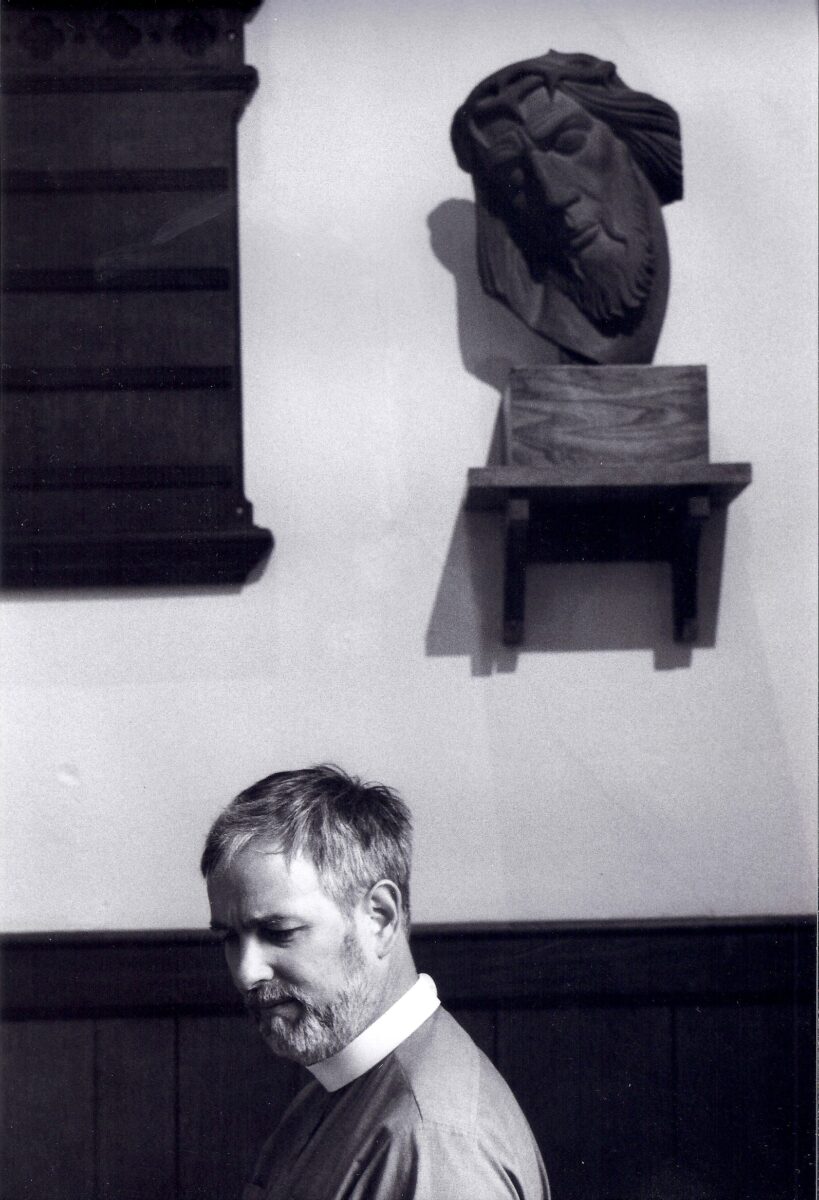

In his office at St. John’s, a somber, haunting portrait by the early twentieth-century French artist George Rouault hangs over a modest desk tucked into a window alcove. How it came to be there is perhaps a metaphor for Jenks’ outlook on faith and his ministry in Thomaston, where he has shown up for 32 years—not just for the church but for the broader region.

Jenks is himself an artist. (He delights in the fact that one of his paintings, “a primitive kind of thing” of Adam and Eve with a naked Eve talking to the serpent, was removed from a Thomaston café following complaints that it was too risqué.) “I was an art major in college and one artist that’s hugely important to me is George Rouault,” says Jenks. “He was a very active Christian in the Catholic Church and in his Miserere series did one particular piece of Jesus as a harlequin as his self-portrait. I redid it in different ways. It was very influential to me.” A woman in the parish had inherited some artwork and gave it to the church; as Jenks was going through it, there was the print from Rouault’s Miserere. “The fact that it’s this one, only God would know, of all the artwork … and God put it in front of me.”

You could say that in 1992, God put St. John’s—and the surrounding community— in front of Jenks. He grew up as an Episcopalian, and after being ordained in Minneapolis on the feast of St. John Baptist in 1985, he served as associate rector at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Newport News, Virginia. Having spent summers in Mid-coast Maine, he couldn’t see himself living there year-round. But someone put his name in for the rector’s job in Thomaston. “I was in this big parish in Virginia, and the rector had left, so I’m in charge of the church and the day school, and it was a circus on every level,” he says. I got a call in the midst of a wild day from St. John’s and apparently, I was one of the finalists.”

You could say that in 1992, God put St. John’s—and the surrounding community— in front of Jenks. He grew up as an Episcopalian, and after being ordained in Minneapolis on the feast of St. John Baptist in 1985, he served as associate rector at St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Newport News, Virginia. Having spent summers in Mid-coast Maine, he couldn’t see himself living there year-round. But someone put his name in for the rector’s job in Thomaston. “I was in this big parish in Virginia, and the rector had left, so I’m in charge of the church and the day school, and it was a circus on every level,” he says. I got a call in the midst of a wild day from St. John’s and apparently, I was one of the finalists.”

When he came to Maine for the interview, Jenks recalled an experience he had from the backseat of a car while living in Ireland in the late 1970s. “There were hills going up with these rock walls. I looked out, and something inside me said, ‘Peter, this is what your home looks like. This isn’t your home, but this is what it looks like.’” Driving along the St. George peninsula, he recognized a familiar landscape. “I looked out the window and I said, ‘This is what I saw years ago. Okay, God.’”

From the outside in

A video retrospective created to celebrate Jenks’ impending retirement traces his long and full tenure at St. John Baptist. There he is officiating multiple weddings and baptisms; playing guitar; dressed up as a chick in an egg; shoveling snow in his robes; marrying his wife, Emily, in front of the congregation; and goofing around with kids. The Carpenter Gothic church in the middle of downtown Thomaston is busy, as Episcopal congregations go these days. “It’s a healthy parish. It is just a jewel of a place,” Jenks says. “Our average attendance is in the 40s and 50s, and in the summer it’s higher. We had more in the 1990s, but it’s still active and very viable. Part of that is continuity. Part of that is because I’ve been here. I will know people when they come back every summer. They know me, and that’s hugely important. I’m known in the community.”

While he describes himself as an “outsider,” in Thomaston and the surrounding area, Jenks is very much on the inside. Over the years he has been involved in prison ministry (before the Maine State Prison relocated from just down the road to Warren), a firefighter, police chaplain, and town meeting moderator. He’s hosted a radio show, acted in local plays, and served on several boards, including for the DaPonte String Quartet and a group that welcomes new Americans.

While he describes himself as an “outsider,” in Thomaston and the surrounding area, Jenks is very much on the inside. Over the years he has been involved in prison ministry (before the Maine State Prison relocated from just down the road to Warren), a firefighter, police chaplain, and town meeting moderator. He’s hosted a radio show, acted in local plays, and served on several boards, including for the DaPonte String Quartet and a group that welcomes new Americans.

When Maine voted by caucus, “I’d put my collar on, and stand in the middle of the room, and shake hands. To me, that’s marketing,” he says. “Nothing to do with politics—it’s like I’m going to go to a place where not many people have a church home. So, they have a connection with me. They know the priest, they’ve met the person, they’ve talked to them. And we leave the church open so people who are out walking in town can use a bathroom.”

Jenks also helped start a program whose influence now extends beyond well Thomaston. Together with Jack Carpenter, a youth development professional who moved to the area from Boston in 1994, he founded Thomaston Trekkers, then an all-volunteer organization with a mission to build connections for at-risk kids.

“My neighbor was a Maine guide, and so I was like, ‘How can we just get some of the people in our community here and go out camping?’” Jenks says. “Because a small town will either be the best place in the world to grow up or hell. We wanted to break that cycle. So, we took the first trip with four boys up to Jackman. And then next six months later, it was a group of girls. All with local support. The idea was, this is our kids, we need to do it.”

Now called Trekkers and headquartered in Rockland, the program is a 501c3 with a professional staff that uses outdoor and experiential education to mentor young people for six years—beginning in seventh grade—and has inspired a similar program for urban youth in Camden, NJ. “It started as this little seed, and the hundreds of kids that have gone through this program had their lives changed because of it,” Jenks says. “The best thing that I did was like, ‘No, this is not a church thing. This is not to draw attention to St. John’s.’ The best thing I could do was get out of the way.”

For Jenks, social justice begins at home—and should always start with Jesus. “We don’t need all these resolutions. We are not the center of the world,” he says. “Dunkin Donuts is more important in my town than any Episcopal church is. My politics are all over the map in different ways, in different times. Jesus may lead you to do something. I’ve been arrested. I’ve done various protests. I’ve done various actions. And if you do pray, thoughts and prayers will lead you to actions.”

Moving on

After he retires, Jenks plans to stay in town, but is sitting loose to what’s next. “I don’t know if I’ll do supply, or interim, or whatever; I think it’s just doing nothing for a bit,” he says. “Something else is happening now; I don’t know what it is. I would like God to see the 10-year plan and have the doors open so I can know, ‘Okay, I’m going this way,’ and the lesson I’m having right now is that the door doesn’t open until you get there and turn the knob.”

After he retires, Jenks plans to stay in town, but is sitting loose to what’s next. “I don’t know if I’ll do supply, or interim, or whatever; I think it’s just doing nothing for a bit,” he says. “Something else is happening now; I don’t know what it is. I would like God to see the 10-year plan and have the doors open so I can know, ‘Okay, I’m going this way,’ and the lesson I’m having right now is that the door doesn’t open until you get there and turn the knob.”

As he waits to see what God will put in front of him, Jenks says there are three “anchors” that help keep him steady. “One is the sense of something sacred, which always helps me see in a different way and pulls me out of my world into a larger dynamic. And is the only thing wider than God’s mercy is God’s sense of humor—God is always laughing at me. The last thread, when the other two anchors aren’t holding (my aunt taught me this), just sing. It doesn’t matter how bad you are. It could be ‘Happy Birthday;’ it could be holding a child and singing, ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.’ Whatever it is, just start coming from your heart and singing.”